Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and his New York City Paleozoic Museum

by David Goldman

First appeared in the Dec/Jan 2003 issue of Prehistoric Times Magazine.

Back to Home Page

|

Introduction Like many of you I too am amazed by the story of how close New York City came to having a Paleozoic Museum built in Central Park. There are many well written accounts which follow the sequence of events as Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins arrives in New York, is invited to build the museum, and then is startled when his work is destroyed by politicians who just didn't get it. What I am going to do here then is not to necessarily tell the story again but to take a look at the view of New York City that Hawkins encountered, show the people he associated with, and to also point out where visitors can go to see for themselves those places still in existence. |

|

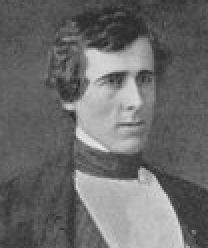

This print of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins is from the

Hawkins Album, archived at the Ewell

Sale Stewart Library, Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. (Used with permission). Note: Their online exhibit is using a version of xml that requires Internet Explorer. |

||

|

|

Wood cut illustrations of Hawkins' Crystal

Palace Prehistoric Animals as published in Johnson's Natural History 1871 and a

nice overall sketch published in Creatures of Other Days 1894

Sydenham Park Sculptures Dinotherium Megatherium

Iguanodon Megalosaurus Hyleosaurus |

|||

|

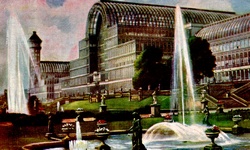

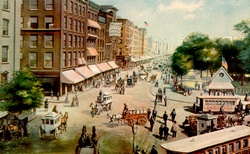

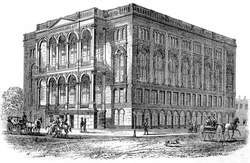

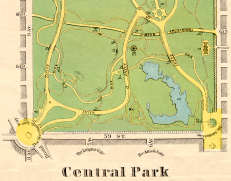

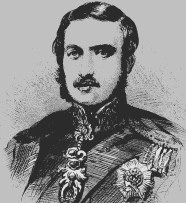

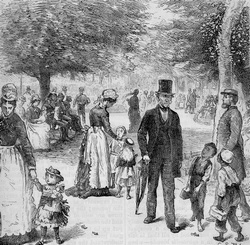

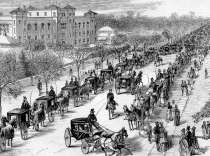

Part 1. Review of Hawkins Days in England He was a terrific artist, and had many commissions. He illustrated scientific works, and put out a few books on how to draw animals. At Knowsley he documented the zoological collection of Edward Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby, for several years. As a commissioner at the Crystal Palace he was known by Sir Richard Owen, and Prince Albert. When they moved the Crystal Palace to Sydenham, Prince Albert suggested that life sized reproductions of the then known prehistoric animals be constructed on the grounds. Even though there was scant material to complete the conception, Hawkins, in his desire to provide Visual Education for the masses, didn't see that as a problem, simply going ahead and putting in a good guess where needed to finish the visualization. The "Masses" would get the idea that there were large strange beasts that once lived here a long time ago. To prepare the molds for these beasts, the sculptor was given a large spacious studio, a wood cut of which was printed in the Illustrated London News of December 31 1853. I've seen this illustration reproduced in many of the articles on paleontological history. None of the small reproductions do justice to the actual art in the newspaper. It's printed full page, measuring 13.5" x 9.5". Find one of these for your collection if you can. Part 2. New York City prior to Hawkins Arrival Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins ran smack into the middle of a great swirl of social development and expansion. The great potato famine was forcing Irishmen to take the option of going to America seriously, and many did, along with great numbers of Germans too. One Irishman who came a little earlier was lucky enough to have had a small inheritance. Alexander Turney Stewart used the funds to open a small dry goods store in New York City. When faced with a financial difficulty he marked all his stock down, put flyers up all over and became famous for selling top quality goods at a wholesale price to all. The first discount store was born. He became fabulously wealthy, even by New York City standards. When his fellow Irishmen needed help he filled a ship with goods to donate and sent it over. And he offered free passage back with promises of jobs to all his Irish compatriots. New York was filling up with Irishmen. A. T. Stewart's wife's cousin married a Judge named Henry Hilton. These two men got to know each other very well and Hilton became Stewarts right hand man. Hilton had studied law in New York City and was certified in the same year as Andrew Haswell Green. That was pretty much all that these two men had in common. Green was more like Hawkins in that he felt educating the masses was an important social need. He had gotten elected to the school board and then was offered school board president. Mr. Green became widely known as a wise user of public funds, spending only where absolutely necessary, and keeping strict account of every penny. As a lawyer he learned his craft in the law offices of Samuel J. Tilden. These two men became the best of friends. Here's a short passage from Mr. Green's Diary "This evening attended a primary political meeting to elect three delegates to Tammany Hall. Met Mr. Tilden there and after he had made a speech and the meeting broke up, we took ice-cream at Alhambra, walked up about Union Park, talking until about eleven o'clock." Instead of taking the School Board offer Green chose instead another offer, the position of Commissioner of the Central Park, which was just beginning its development. The park was originally planned to be placed at Jones Woods on the East Side of the City. Henry Hilton fought for the neighbors opposed to this and won. The park, it was then decided would go in the middle of Manhattan Island, to be called simply The Central Park. Commissioner Green decided to have a competition for the design of the park. One of the men working as a park officer, Frederic Law Olmsted teamed up with Calvert Vaux, and offered the winning plan. You can still see this drawing, now 150 years old, on display. It's in a building that has become central to this story: The Central Park Arsenal. This structure was put up in the 1850's for the New York National Guard, and when the land was taken by the state for a park, this building came with it. Right from the earliest plans, the Arsenal was conceived to be some sort of museum. Donations of all sorts of objects were sent and stored there, even living animals. A brief description of the state of this building is found in the Department of Parks report for 1871.

"A limited space of the first story of this building was

occupied by a number of clerks. A small part of the basement (damp and unsuitable as it was) was used by the Central Park Police. The whole building was offensively objectionable. Various animals were confined in the basement and on the first floor, with their cages in a state of great insecurity and danger. There had been no extra ventilation furnished to this building from the time it had been used as an Arsenal, and it's unwholesome condition was apparent to sight and smell." Andrew Green wanted to include in the park a museum of some sort, but it just wasn't clear yet what it was going to be. Already in the northern part of the park was an old empty Convent (St. Vincent) that became the residence of the park planners and their families. The old chapel became the home to the works of a recently deceased sculptor. PT Barnum had his museums, but they were more of a collection of strange and interesting items, not necessary science, or ordered and not what could be said to represent the City of New York. Many natural history collections were in private hands, birds, butterflies, minerals, all owned by people expressing a willingness to donate them if only a suitable place could be found in this city. Barnum's museum's were destroyed by fire twice. This may be a good place to introduce another important person to this story, one of the firemen rushing his team to the burning buildings, William M. Tweed. He was a natural leader, large, friendly, rowdy, and boisterous. He put together "The Big Six" Fire Engine Company, which launched his career into city politics, gaining one position, then another and another. Even though he was elected to Congress, he found that City and State politics was were his heart, energy, and talent was. Tweed made himself the champion of the thousands of new Irish immigrant voters, offering jobs, social services, and helping them work there way through he maze of government bureaucracys. The working poor Irish and Tweed were a team, helping each other get what they needed and wanted. Part 3. Hawkins Comes Over From England To get from England to New York City in 1868 would take about 10 days travel over the Atlantic. Crossing was done by either those beautiful sleek tall masted Clipper Ships, which were just on the way out, or by the new Paddle Wheel Steamers. Hawkins would have had a small room, and probably a roommate or two. He would have landed at the docks and found a coach or perhaps knew his way to take a Stage or Omnibus uptown to his room. The address he gave in his letters to A. H. Green was No. 1 Irving Place. This was no random choice. Situated 1 block east of Union Square, it was right in the very center of New York City in 1868. And it was a neighborhood of the rich and famous. This was a very fashionable place to live, with beautiful small hotels and private residences all around the small cozy park. It appears that Hawkins planned well, for just a few blocks south was the Cooper Union building, where he gave several lectures, and just a few blocks north was Madison Square, home to the Lyceum of Natural History at 58 Madison Ave. Both of these venues were within walking distance, or a short Carriage/Omnibus ride. In his neighborhood was the Academy of Art, and restaurants and small theaters. The park was well known and was frequently shown in the local press. There were no elevated trains yet, and wherever Hawkins went the streets would have been crowded with horse and wagon traffic, and pedestrians. Almost all scenes of the city from this period show the streets packed with activity. If you go to 1 Irving Place today you'll find a skyscraper of apartments. The old block was torn down in the mid 1980's. However much around the new building is as it was in Hawkins day. The Academy of Art still stands, as well as many private homes and small hotels. Union Square park, which we may assume Hawkins spent a little time in, is still available to comfort the neighborhood. The building Hawkins stayed in had it's picture taken around 1940 when New York City hired photographers to snap all the tax properties in the city. Thus we have this shot of 1 Irving Place, showing a highly remodeled structure. Nevertheless, one of those windows could have been where Hawkins stayed. Part 4. Lecturing The first place on record that Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins spoke in New York was at the Lyceum of Natural History, which had its rooms at 58 Madison Avenue. This address is 1 block north of Madison Square, another of the City's little parks still in existence. This was just two days after arriving, and he gave a lecture on the importance of Visual Education for the masses. He then offered a series of lectures at Cooper Union, an establishment built by Peter Cooper, the industrialist, inventor (first steam railroad engine, transatlantic cable). Attendance was reported to be over 3000 people. On another occasion, Horace Greeley, the newspaper owner/editor of the Tribune, invited Hawkins to speak at Association Hall where Greeley was presenting a large bone. Hawkins clarified for all that they were looking at a part of the Great Woolly Mammoth. From New York to Chicago, Hawkins gave his lectures on the Unity of Design, Natural History, Visual Education, and his ideas regarding the nature of evolution. The Cooper Union building and lecture hall where Hawkins spoke is still a prominent educational institution of today's New York City. The visitor can see the building and lecture hall nearly as Hawkins did. Part 5. Begins Commission to Build Paleozoic Museum Andrew Haswell Green, now the Park Commissioner, offered Hawkins the opportunity to place in Central Park a group of life sized prehistoric animals, much as he had done for England at Sydenham's Crystal Palace. Hawkins accepted the commission and began the search for appropriate American Prehistoric creatures. An 8 hour train ride brought him to Washington DC, and he traveled as well to Chicago, and to Philadelphia. There, at the Academy of Natural Sciences he met Edward Drinker Cope and Joseph Leidy, and found the bones he was looking for. Hawkins used the material to put together the first ever skeletal reconstruction of a dinosaur in the world, the Hadrosaurus. A plesiosaur in it's matrix arrived during Hawkins stay and he helped remove the bones. Cope sketched the creature and others they had that Hawkins was going to reconstruct for the Paleozoic Museum. A picture of the group was published along with Cope's articles in the American Naturalist for March 1869. Part 6. The Arsenal Studio in Central Park Back in New York, all Hawkins needed was a large studio, like the one he had at Sydenham, to construct the models, molds and casts. Andrew Green looked to the catch all structure, the Arsenal , as a temporary solution until the Paleozoic Museum foundation could be made ready. This building was nothing at all like what Hawkins needed or expected, but he went along. Several images of what the building looked like at the time are available. There is a lithograph of Hawkins studio in the 12th annual report of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park, a photograph of the studio is in the Hawkins Album at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and a wood cut was printed in Harpers Weekly, August 14 1869. The Arsenal building is a must see today for anyone interested in the history of paleontology. It has been remodeled several times since Hawkins' day, and is now covered in brick instead of stucco. Its still a mystery as to where in the building Hawkins had his studio. The open spaces have been divided up into offices, and only one main office and a conference room are large enough to give a sense of what it may have been like for Hawkins. The surroundings, being able to step outside and be right in Central Park, must have been a pleasant respite from some otherwise difficult working conditions. Part 7. Beginnings of the American Museum of Natural History In December of 1869 Andrew Haswell Green was part of a group of men who were now committed to establish in New York City a Natural History Museum worthy of this metropolis. Green, along with some of the most prestigious names of the city, the first board of the AMNH, petitioned Green in his role as the park Commissioner to use the Arsenal as a holding place for a vast and growing collection of natural history objects. They were interested in using the Arsenal until a more suitable space could be built. Green decided to make the arsenal available to the AMNH and asked Hawkins to move his models and molds into a temporary shed nearby, being promised that the foundations for his Paleozoic Museum will be ready soon. The arsenal began overflowing with natural history collections and objects being purchased and donated. Part 8. A Year of Frustration leading to the end Remember William Tweed? Since the 1850's, while Hawkins was building up prehistoric animals and visually educating the masses, Tweed was growing in political strength. He had become the leader of the powerful Tammany Hall political society, and pushed through a new charter for the city of NY giving him and his associates unchecked power to borrow money and make contracts. Two months after the founding of the American Museum of Natural History, Tweed made himself commissioner of public works, his associate Sweeny became the head of the parks department and they gave A. T. Stewart's trusted companion Henry Hilton the job of overseeing Central Park. Hilton assured the AMNH board that the arrangements previously agreed to for the arsenal would still be in effect. He also had the arsenal thoroughly cleaned out, refinished, and presented the museum with new display cases. A. T. Stewart donated $2,500 to the museum. Hawkins meanwhile, was put to work on other projects. In November Olmsted and Vaux resigned their Park commissions in disgust stating that politics had made the situation intolerable. In December, the Tweed Park Commissioners discontinued Hawkins contract. In April 1871 the American Museum of Natural History had a spring reception at the Arsenal showing off the new Museum's collections. May 3rd 1871 was a pleasant clear day according to Prof. Drapers weather station on the arsenal. A great day for spring cleaning I suppose. Henry Hilton ordered all of the molds, models, and casts from Hawkins temporary shed to be taken out, broken up and discarded. According to Hawkins they were carted up to Mount St. Vincent and buried. Part 9. Fed Up Citizens Take Control of the Cities Finances Harpers Weekly and then the New York Times began a campaign to make the public aware of the disreputable ways of this current New York City Government. Thomas Nast was lampooning the politicians and the NY Times was printing stories of graft and the abuse of power. Samuel Tilden helped form a group to use the law to fight Tweed. Eventually it all came to a head when an injunction was arranged to stop the city from any more borrowing. On September 16th 1871, the Ring's City Controller, John Connally, agreed to let Andrew Haswell Green take his place, and Green proceeded to try and salvage what was left of the city's finances. Shortly thereafter Henry Hilton and Park Commissioner Sweeny resigned too, returning complete control of the park back to Green. Part 10. Disbelief, Anger, Sorrow and Moving On The news of the destruction of Hawkins project was reported on for the next several years. It even appeared to some that the AMNH may have contributed to the downfall but that was not the case. Director Henry at the Smithsonian said he would have gladly purchased all of Hawkin's material. And although the loss was a stunning blow, Hawkins was not without resources. He still was able to produce 3 more skeletal reconstructions in the next several years. As for getting re-commissioned now that Green was back in charge, that was not going to happen. Andrew Green had his hands full trying to scrounge up enough cash to pay off the city's depts. Workers weren't getting paid, and contracts were all put on hold until Mr Green could validate any and all payments. Near riots were encountered daily, and although the banks were very hesitant to loan more money to the city, they loaned whatever amount Green wanted on the basis of his good name alone. In this environment Hawkins was plain out of luck. The building foundation that was started was plowed over. If you go to 63rd street and Central Park West you can see the area where the Paleozoic museum was to be. It's difficult to know for sure it's exact location, but a good guess would be the base ball fields by 63rd street. Perhaps someday a geologist with one of those ground blasters will give it a shot to try and discover the location of those concrete foundations. Then at least we can put up a plaque or something. What happened to the remains of the broken up models is also a mystery. Hawkins was quoted in a NY Times article saying that Col. Stebbins dug up the remains buried by the old Convent but found them to be broken up into thousands of pieces and useless. Writing in 1894, Rev H. N. Hutchinson stated in Creatures of Other Days that he heard the pieces were tossed into the lake. Somehow the story changed from buried at the Convent to dumped into the lake. The buildings of the old Convent of St. Vincent were turned into a hotel, but that all burnt to the ground on January 2 1881, and other structures have been built on the site since. There seems to be little chance that any remains of Hawkins' work could still be found. Part 11. Follow Up Henry Hilton became the only beneficiary of the Stewart millions, making him one of the wealthiest men in the country. Boss Tweed was convicted and died in prison in 1878. Samuel J. Tilden became Governor of New York and then lost the race for President to Rutherford B. Hayes. Horace Greeley, who shared the stage and a Mammoth bone with Hawkins, ran and lost the race for President against U. S. Grant. Andrew Haswell Green went on to be a great civic leader and is known as The Father of New York City. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins made one last failed attempt to collect pay owed him from his contract to build the Paleozoic Museum . He continued to sell his Hadrosaur skeletons, published more art books, and lectured. Here’s an interesting quote from The New York Times: “The lecturer in conclusion said he did not like the theory of evolution because it mars belief in the purpose of the Almighty, and because it murders poetry, without which life would be little worth living.” Part 12. A Couple of What Ifs… 1) How do you destroy a several ton clay model of a Hadrosaur? Maybe they just moved it into some long forgotten storage space. And then I saw a familiar looking image in Frank Leslies Popular Monthly Magazine of April 1891. In an article about the American Museum of Natural History, there was a picture of Hawkins’ Hadrosaur. Same view, same pose. But the article didn’t mention the picture, so it may have been a stock wood cut. But I wonder if in some long forgotten back room at the museum, covered up with sheets like an old grand piano in some horror movie set, there lies beneath a giant sculpture in clay of… 2) Around 1879, just before Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins went back to England, a young 4 year old Charles R. Knight would visit the park and zoo with his father and sit quietly and draw pictures of the animals. Do you suppose that young boy was ever approached by this distinguished looking Englishman, did Hawkins ever tell the kid how wonderful his drawings were? That perhaps someday he would grow up to be, like him, a great illustrator of prehistoric animals?

All the work done to have paleontology displayed in NYC came to fruition with this, shown here about 1900, the American Museum of Natural History. From a single building it expanded until now it is an immense undertaking requiring Doctorate Offices in all Natural History fields and probably uses the best cleaning companies in NYC, along with maintenance and landscaping professionals to maintain the acres of display space. |

|

Hawkins Illustration for Earl of Derby  Crystal Palace  Crystal Palace Interior  Hawkins Sydenham Studio  Andrew Haswell Green  Jones Woods  Calvert Vaux  Central Park Arsenal Interior  Mount St. Vincent  Boss Tweed  Street Sweepers  Clipper Ship  Broadway New York 1916  14th Street New York City 1897  Cooper Union New York City 1868

Peter Cooper Horace Greeley

Joseph Leidy Edward Drinker Cope  Cope's sketch of American Prehistoric Animals

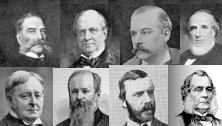

Central Park Arsenal Recent Photo - 1  Central Park Arsenal Recent Photo - 2  Paleozoic Museum Interior Sketch  Some original AMNH Board Members Morris K. Jesup, Robert I. Stuart, J. Pierpont Morgan, John David Wolfe, Joseph A. Choate, Charles A. Dana, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., Benjamin H. Field  Inside at the Spring Reception

Green in 1871 Thomas Nast  Joseph Henry  (Revised) Map - 8th Ave is now Central Park West Paleozoic Museum was located near 63rd St.  Mount Saint Vincent after the fire 1881 |

Sir Richard Owen  Crystal Palace Dinosaurs  Prince Albert  A. T. Stewart  Henry Hilton  Samuel J. Tilden  Central Park Carriages  Central Park Squatter Community  Frederic Law Olmsted  Central Park Arsenal  P. T. Barnum  Barnum's Museum  Fire Brigade

New York City from Brooklyn  Omnibus Interior New York City 1891  1 Irving Place New York City 1940  Union Square Manhattan New York City 1878  Cooper Union Lecture Hall New York City 1865 (Another view of the lecture hall)  Overland Railroad  Hawkins first Hadrosaur  Hawkins Studio at the Central Park Arsenal  Central Park New York in Hawkins' Day  Tweed Associates Sweeny, Connolly, Mayor Hall, Gov. Hoffman  Spring Reception at the American Museum of Natural History in the Central Park Arsenal  Tweed and Company in Nast Cartoon  Baseball fields at 63rd St. Central Park West Is this the site of the Paleozoic Museum?  63rd Street Sign  Model of Hadrosaurus |